As tech hubs beyond the established coastal ecosystems continue to gain visibility, economic developers and community leaders are looking to tap into the innovation drivers present in both urban and rural economies. The research and development (R&D) activities of academics and companies represent key contributions to economic competitiveness. Common measurements of innovation include patents, licenses, and capital availability. Communities looking to bring additional capital into their communities for innovation should not overlook the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs as accessible sources of federal funding. Both programs have key similarities in structure and purpose. However, SBIR has fewer requirements and more funding available, making it more accessible for small businesses.

About SBIR/STTR

While federally funded R&D activities are mostly conducted by government labs, academic institutions, and large corporations, small businesses have access to dedicated federal research and commercialization funding through SBIR and STTR. The SBIR and STTR programs, created in 1982 and 1992 respectively, require agencies with sizable, extramural R&D budgets[1] to set aside part of their funding to engage small businesses in federal research. Both programs support the innovative activities of small businesses whose R&D align with national priorities at various stages of research commercialization.

Every agency’s SBIR and STTR programs operate on a three-phase funding structure. Each phase represents a new competition, proposal requirement, and contract amount. Phase I provides funding at the feasibility study level of research to determine scientific and technical merit. Typically, Phase II eligibility depends on receiving a Phase I award and provides additional funding based on the project’s continued relevance to federal priorities, commercialization progress, and private investment. Phase III funding does not have a dedicated source of funding but allows for additional awards to be made from non-SBIR/STTR dollars to continue the project’s commercialization.

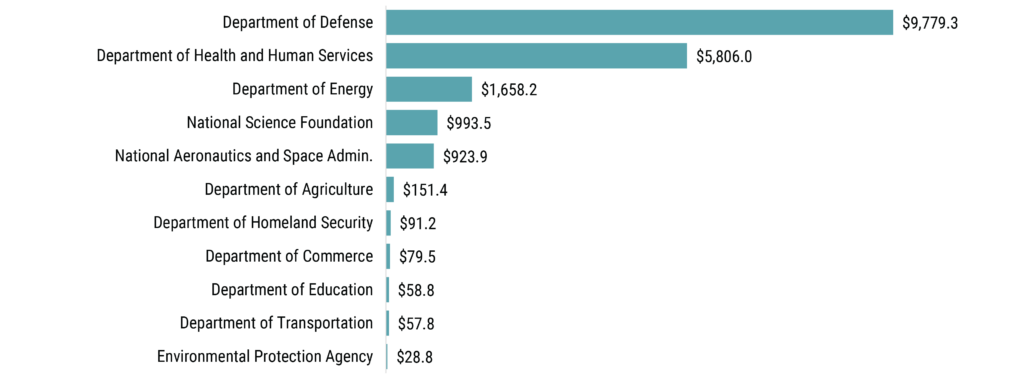

Eleven federal agencies are required by statute to set aside at least 3.2 percent of their extramural R&D budgets for SBIR programs because those budgets exceed $100 million.[2] The size of SBIR/STTR budgets is proportional to the size of federal agencies’ overall R&D budgets. As a result, the Department of Defense (DoD) represents nearly one half of all SBIR/STTR funding disbursed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. SBIR & STTR Awards to Small Businesses by Federal Agency

Awards by dollar amount (in millions US$), 2019-2023

Source: US Small Business Administration, TIP Strategies, Inc.

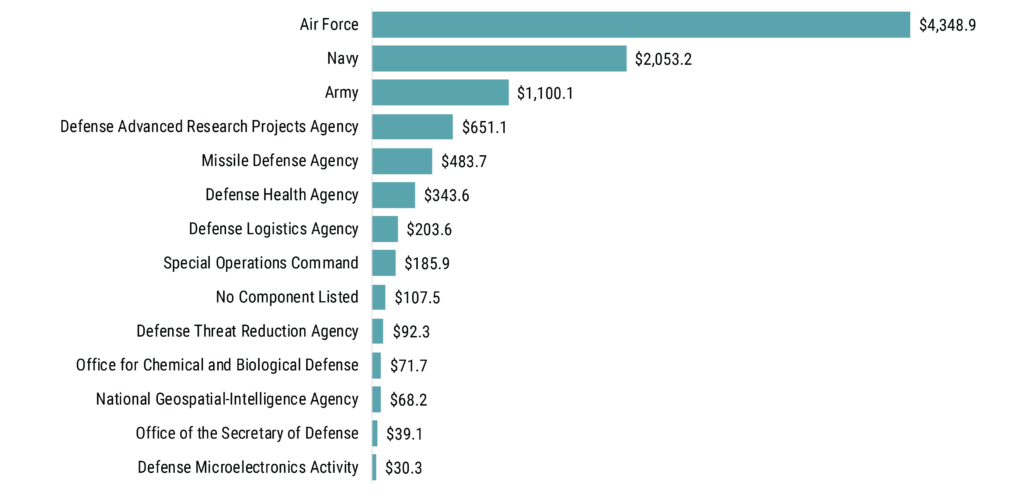

The outsized share of total SBIR/STTR dollars set aside by the DoD compared to most other agencies has important implications for both prospective awardees and the economic development organizations that support them. Thirteen DoD components participate in SBIR, with one component, the Department of the Air Force, representing approximately 44 percent of all DoD SBIR/STTR funding disbursement (Figure 2).

Figure 2. SBIR and STTR Awards to Small Businesses by DoD Component

DoD awards only, by dollar amount (in millions US$), 2019-2023

Source: US Small Business Administration, TIP Strategies, Inc.

In the DoD’s case, SBIR/STTR programs leverage small businesses as a source of R&D for new military and defense capabilities. Proposals are weighed on their demonstration of commercial feasibility (and traction, in later stages) as well as technical feasibility. The DoD’s investment thesis for SBIR/STTR dollars is to invest in dual-use technologies—those with both commercial and military use cases.

What It Means for Practitioners

There are at least three takeaways for economic development practitioners. First, the DoD is big, but it isn’t the only agency providing SBIR/STTR funding. Efforts to help R&D-focused small businesses access SBIR/STTR dollars should align with a community’s existing strengths, including its industry clusters. This may translate to developing better familiarity with certain agency programs and offices over others. But the DoD’s global reach and the breadth of its mission also can have relevance for many sectors. Critical examples include advanced manufacturing, healthcare devices, energy storage, and cutting-edge information technology like artificial intelligence.

Second, tracking SBIR/STTR awards in your community provides an important source of business retention intelligence. Which R&D-focused small businesses are gaining federal traction, if any? Which industry sectors do they represent, and what challenges do they experience? Do they get started in your community, but end up leaving? What options are within your control to address retention issues? For communities lacking in venture capital, building the density of investment opportunities for these firms is especially critical to increasing overall capital availability for small business innovators.

Third, economic developers can strengthen R&D-focused entrepreneurs in the same manner as other kinds of small businesses by providing education, resources, visibility, and connections that foster their growth. Practitioners can also advocate for initiatives that leverage these federal dollars. From a policy perspective, the cost of proposal service providers can be subsidized, a practice implemented in Michigan. Small businesses rarely have the dedicated human or financial capital to fund a grant writing position in general, much less specific to the SBIR/STTR process. As another example, states such as North Carolina have legislated SBIR/STTR matching programs. And, some local governments such as the City of San Antonio have started providing matching grants to support small business innovation.

When it comes to improving a community’s innovation assets, economic development practitioners can only do so much to influence postsecondary science and engineering programs or to increase the presence of venture capital firms. However, supporting R&D-focused small businesses with accessing federal SBIR/STTR dollars is a specific strategy that fits squarely within the realm of business development—helping to grow a community’s innovation assets and, thus, broader economic competitiveness.

[1] An agency’s extramural R&D budget reflects funds allocated for/paid to outside institutions or individual investigators for research activities conducted under a contract, grant, or cooperative agreement.

[2] The requirement to operate an STTR program is an extramural R&D budget of $1 billion, which applies to 5 agencies: Department of Defense, the Department of Energy, Health and Human Services, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and National Science Foundation. STTR has a lesser minimum set-aside requirement (0.45 percent), resulting in less total STTR funding overall compared to SBIR.